Here's some more in-depth information about the different aspects of NLP that you can learn during Practitioner training.

NLP is a study of how we can use language to map the connections between internal experience and external behaviour.

Why is that worth learning about?

Simply, because your internal experience defines everything that happens in your life. It defines your relationships, your communication, your goals, your achievements and your frustrations. Your internal experience is your map of the world, and your behaviour is an organised attempt to shape that map to your needs. Therefore, everything that you do, and every result that you get, is a direct result of what you believe about the world.

That internal experience is hidden from you. It is not a window through which you view the world; it is the world, as you know it.

The differences between that private world and the outside, physical world hold the key to your direction and achievements in life, and NLP is one way of understanding and refining that connection.

While NLP is often broken down into categories of techniques, once you begin to learn it, you'll quickly discover how all of the different techniques are interwoven. The reason for this is simple; NLP's techniques are built up from some very simple first principles, and when you study those principles, you'll see how everything fits neatly together.

Jump to a topic:

Subjectivity and NLP's model of 'reality' - Back to the list of topics

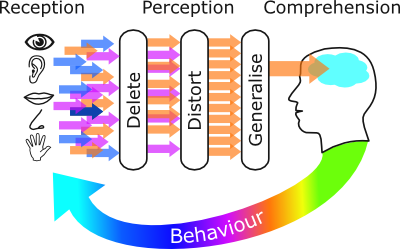

An important concept in NLP, and in other psychological and philosophical theories, is that we construct our experience of the outside world by piecing together snippets of information gathered by our senses.

Because there is far too much information available, we have to reduce it down in order to make sense of it. Just go into any busy room and try to listen to every conversation at the same time to experience the potential sensory overload that we all face, every moment of every day. Even if you're sitting somewhere quiet right now, there is a huge amount of information that your brain is filtering out. For example, can you notice the temperature of the air? What can you see around you that is red? How do your feet feel? What sounds can you hear?

Even our senses, which are concerned with the reception of information, don't have access to all the potential information that exists in the world. We can only see and hear in a very narrow range of frequencies that coincide with the characteristics of sunlight and air. Our sense of smell is generally rather poor. We cannot directly sense magnetic or electrical fields, ultra-violet light or the rotation of the Earth, yet the limited information that is available to us is still too much to cope with.

In order to reduce this overwhelming amount of information so that we can focus on what's important, our brain uses three filtering processes.

The first filter deletes anything that is not within our focus of attention. It's also influenced by our beliefs, for example allowing your car keys to disappear before your eyes when you are convinced that you've misplaced them.

The second filter distorts the world so that it appears how you think it should be. For example, if there is someone at work who you can't stand talking to, you probably distort the way their voice sounds. You have probably also distorted many of your memories to exaggerate how they feel to you.

The final filter generalises information and forms rules. We couldn't survive without generalising. Our ancestors couldn't test every sabre toothed tiger to see if they were all dangerous, and we don't want our children to wonder whether every road that they cross is dangerous or not.

These sensory filters form our perceptions and most people, most of the time, confuse their perceptions with reality. A lifetime of perceptions create what you know through the processes of comprehension, and your experiences form your attitude and personality, which drive your behaviour.

Your behaviour influences and changes the outside world, which feeds back in through your senses.

Therefore, your senses are not a one way street; they are part of a continuous flow of information from the outside world into your mind and from your mind back to the outside world through your thoughts, words and actions.

In NLP, we often refer to this lifetime's collected experience as a person's 'map', taken from the saying that "the map is not the territory".

When a person's map differs significantly from the territory, the outside world, they cannot function effectively. They are unable to deal with the unexpected and they particularly struggle to make sense of and relate to other people. Physical objects are reasonably reliable and constant, but people are ever changing and growing, and so our 'map' of other people must be open to changing and growing too.

And if that's not already a lot to take in, consider this. If you were to calculate the resolution of your eyes in the same way that you would for a digital camera, you would discover that your eyes are physically incapable of resolving enough detail to even read these words. So how are you able to see in such detail? Clearly, vision is more than just a physical process...

Imagine using a satellite navigation system that had a map that was ten years out of date. Where would it take you? Dead ends? Would it take you through congested town centres rather than round the bypass? Would it take you on narrow country lanes instead of a new motorway?

It might sound like an impossible example, yet the reality is even worse. People have driven the wrong way on Motorways because their 'sat nav' told them to do a 'U turn'. The number of accidents involving trucks stuck under bridges has increased because of 'sat nav' systems with incorrect information. One man even followed his 'sat nav' when it instructed him to drive over a bridge. The bridge was, in fact, a car ferry and the man drove his car off a quayside. It's difficult to understand how these drivers couldn't see that the 'sat nav' was wrong. It's hard to believe that they couldn't just use their own eyes. Yet we all do this, every time we rely on our own out of date maps and choose to ignore the information that the outside world is giving us.

Many NLP techniques simply recover the information lost within this filtering process so that a person can update their map of the world, gaining more useful perceptions and behaving more appropriately and effectively in situations that they previously found difficult to manage or control.

When people do 'wake up to reality', they often do so with a shock, yet it doesn't have to be that way. NLP gives us a set of tools and techniques that help us to update our maps so that we can live more in the real world and enjoy meaningful and satisfying relationships with the people we share it with.

State - Back to the list of topics

State isn't just about how you feel, it's your entire present physical and mental condition, so you might be tired, happy, curious, careful or fascinated - all of these are states.

The two key ways to quickly influence your state are through your physiology and your focus of attention.

People have all kinds of methods and routines for controlling or maintaining states. Perhaps you have a routine for getting ready for work, or for going out on a Friday night. Perhaps you have a lucky charm or item of clothing that helps you get into a certain state. Perhaps you can just think of a state and you're there. The reality is that everyone has total control over their state, yet most of the time we just go with the flow, letting external events and people cheer us up or put us down.

Your state defines the meaning you make of the world, the choices you make, the risks you take and the language you use. The differences in your behaviour between a great day and an awful day may be tiny, yet they add up over time creating a state that builds throughout the day, reinforcing itself.

When you wake up, knowing it's going to be a bad day, you program your sensory filters to notice things that go wrong. Anything that goes well is set aside as an accident or coincidence. When you plan for bad things to happen, they often do.

When you wake up, knowing it's going to be a great day, you notice everything that goes well for you. Anything that doesn't go your way is set aside as just a temporary setback. When everything seems to be going your way, it probably is.

You might say that you can't predict or control what happens to you, and you might be right in saying that. What you can control is your response to what happens. Here's an example.

A salesman leaves a message for a customer to call him. After two hours, the customer hasn't called back. The salesman knows that the customer always returns calls promptly, therefore something must be wrong - the customer must be avoiding the salesman. Self doubt starts to creep in and the salesman's state changes to reflect his negative mood. When the customer finally calls (he had left his mobile at home) the salesman's voice tone reveals his state and the customer thinks something is wrong. The customer's state changes accordingly, confirming that salesman's suspicion and they enter a 'vicious circle'.

The only thing that the salesman can say for certain about this situation is that he has not spoken to the customer since leaving a message. The salesman's response presumes that he has read the customer's mind; the customer has heard the message and has made a conscious decision to not call back. None of this is true, so it's just as acceptable for the salesman to imagine the customer going to the dentist, or just taking a quiet afternoon out to make an important decision. Neither this nor the pessimistic version is 'true' in an absolute sense, so which is the more useful to believe?

Let's say the customer has gone away to decide whether to buy the salesman's product or not, and currently the customer is undecided. When the customer calls back for more information, the salesman's state could be the deciding factor. You may think that no customer would make a decision so lightly but in fact we each do exactly this - we buy from people we like to do business with. A friendly voice on the end of the telephone could be all the customer needs to decide. Conversely, a negative or pessimistic voice could influence the decision by making the customer more aware of their doubts.

Your state is a filter through which you experience the world, and it's a mechanism by which the people in that world experience you. A NLP Practitioner can both influence a client's state and also give the client tools to manage their own state so that they can make better informed decisions about what is happening around them and behave more appropriately and effectively.

Rapport - Back to the list of topics

Watch two people, deep in conversation, and you will see a number of things happening. You'll see them touch their hair or pick up a cup at the same time. You'll see them laugh at the same time. You'll hear their conversation naturally ebb and flow, and you'll hear them talking at the same volume and pitch. It's as if they're in a bubble, separate to the rest of the world.

This is rapport.

Rapport isn't something you do - it's more like a measure of the quality of a relationship.

You can think of rapport as being a conduit for effective communication. In general, in most situations, it is more useful to have rapport than not. Most of the time, we get into and out of rapport with people unconsciously, so our beliefs and thoughts are revealed non-verbally, regardless of our efforts to hide our true feelings. Regardless of what people say, they will show you who and what they agree and disagree with.

When two people are in rapport, they are influencing each others' thoughts and feelings. When one feels angry, the other feels angry. When one feels relaxed, the other relaxes. When you're in rapport with other people, you are influencing the way that they feel - their state - and that in turn influences how they interpret and respond to their interaction with you.

In a therapeutic or counselling setting, rapport is vital to develop trust and open communication, yet the counsellor must always stay in control, otherwise the client's issues can easily transfer to the Practitioner.

One important thing to understand about rapport is that you can choose the people you want to get into rapport with. If you feel that a salesman is being a bit too persuasive, or that someone secretly disagrees with you, even though they say differently, then it's worth having a quick check of your own feelings and intuitions.

In almost all NLP training courses and corporate 'communication skills' programs, people are taught to develop rapport by 'matching' or 'mirroring' another person's posture and actions. There are certainly some interesting things you can learn from doing this, and in a counselling or coaching situation it can be very valuable. However, in other situations, this approach can be contrived and obvious and can do more harm than good. If you get on with someone, you'll be in rapport with them. If you're not in rapport, there's probably a reason for that and you should pay attention to what it is.

On our NLP Practitioner program, we don't waste time learning how to get rapport, because you're already good at that. With us, you'll learn how to manage rapport - far more valuable for you and your clients.

Outcomes - Back to the list of topics

You'd be surprised how many people don't have a clear idea of what they want. They're not too fussed, just get them anything, they don't mind. Until you get back from the sandwich shop and then they suddenly know exactly what they want - and it isn't what you bought for them. And some people know exactly what they don't want, yet excel in achieving exactly that. When you have a very clear set of outcomes, every action and thought reinforces those outcomes and takes you a step closer to achieving them.

When you don't have clear outcomes, your thoughts and actions tend to be more random, so you have to think consciously about what you do, and you have to waste time correcting actions that take you in the wrong direction.

Frequently, people have a very clear idea of what they don't want, and they only know when things are going wrong for them. They tend to bounce from one wrong course of action to the next, never settling on a clear direction.

Most people think that they set clear goals, yet mostly these goals are not phrased in a way that your brain understands, so they're actually quite useless.

A goal like "To complete my project by September 1st" sounds very specific, but it really doesn't mean much to your brain. For a start, different people each have a different definition of 'complete'. Although we use dates and times as fixed, absolute markers, your brain treats them as very elastic concepts because we all have a different way of coding and representing time. In particular, the concept of 'now' is different for each of us.

You may have come across SMART objectives at work. With SMART, you make sure that every goal you set is:

Specific

Measurable

Achievable

Realistic

Timebound

In NLP, we have a different way of setting goals. We call a goal an 'outcome' because it is the result of behaviour, and we apply four simple criteria to the outcome. When an outcome meets those criteria, it is said to be 'well formed', so in NLP, goals are called 'Well Formed Outcomes'.

Well Formed Outcomes are designed to adapt to a changing world as you move towards your goal, and they are designed to get you to take action, continually, in pursuit of your goal.

With a Well Formed Outcome, you always move forwards. You may or may not end up where you first thought, but that's always a good thing when the territory is changing so quickly.

We are goal directed animals, and we act in pursuit of goals, both large and small. NLP offers a way to access those natural resources so that you can achieve goals that lead you more directly to the life you want.

As Louis Pasteur said, "Chance favours the prepared mind".

Meta Model - Back to the list of topics

One of the most important ways to apply NLP in a therapeutic or coaching situation is to help a client form a more complete and accurate map of the world. There are a number of NLP techniques for doing this, and perhaps the most powerful, flexible and misunderstood is the Meta Model.

Meta just means 'above' or 'higher', so the Meta Model is simply a collection of other linguistic models.

From role models such as Virginia Satir and Gregory Bateson, the Meta Model was created. Simply, we construct sentences which are grammatically correct yet which delete, distort or generalise information. For example, if I tell you that you shouldn't eat chocolate, it's bad for you, you might believe me. If I tell you that you shouldn't trust salespeople then you might believe me too.

Are those beliefs useful? Is it more useful that you also know how I know that, so that you can decide for yourself? Parents pass on beliefs to their children, and some are useful, some are not. The Meta Model therefore allows you to explore and unpick beliefs, assumptions and rules that have become accepted as facts.

The Meta Model is based on linguistic structures which are not specific to NLP, you'll find them in everything from books on transformational grammar to school books. However, what is relevant to NLP is the way that those rules are connected to a person's experiences and behaviour.

According to the theory of 'universal grammar', we are born with the 'hardware' for language, which results in all languages in the world, even those found in remote valleys that had no contact with other cultures, following the same basic structure with a gramtically correct sentence following either a Subject Verb Object (SVO) or Subject Object Verb (SOV) word order.

The theory perhaps began with Roger Bacon, a 13th century English philosopher, who noted that all languages are built upon a common grammar. The idea was popularised more recently by people like Noam Chomsky, Richard Montague and Stephen Pinker, from the 1950s onwards.

We often communicate so lazily, relying on other people to fill in the gaps. Sometimes, when they can't, we get frustrated, perhaps saying, "You know what I mean!" Do you know someone who often says, "Can you pass me the thing?" or "What's going on with that project?"

In NLP, we use the Meta Model to help clients to be very specific about their intentions, needs and experiences. This puts them more in touch with the outside world, and that helps them to make more useful and valuable decisions.

Therefore, becoming familiar with the Meta Model patterns and listening out for them in people's language is a good way to train yourself to notice the way that people structure their experiences, and that is vital in developing your ability to help people change those experiences and then their behaviour.

Milton Model - Back to the list of topics

Milton Erickson was a Hypnotherapist in Arizona. He can perhaps be credited as the person who made hypnotherapy acceptable in western medicine, using it in a wide range of situations and helping patients that other therapists had declared 'incurable'. Erickson had suffered from polio in his early life and found himself able to spend many long hours paying attention to the effect that words had on people.

Erickson's language was structured to gently influence the listener, almost like hypnosis but without the stereotypical 'trance'.

In a normal conversation, language has both structure and content. The content gives you facts and the structure connects those facts together into a story.

For example, if a story contains the facts 'cat', 'dog' and 'tree', there is nothing to tell you what is actually happening. The chances are that you have already imagined what is happening in this story, so your mind has unconsciously filled in the missing information based on your prior experiences.

NLP's Milton Model of language works in this way, giving you the structure but no facts. The listener has to insert the missing information from their own experiences and the result is something that is absolutely unique to each listener.

This process wasn't invented by Milton Erickson, he was simply the role model for it in NLP. If you listen to any statement prepared by a politician, you may hear something similar. For example:

"People will understand that the solutions to these kinds of problems are to be found not in the past but in the future, and everyone will appreciate what a difficult task this can be. You can also be absolutely certain that the government we have now is in a far better position than any other to tackle these problems and to resolve them in a way that is economical, effective and respectful to the local community."

Does that sound familiar? Perhaps you remember hearing that before, about asylum seekers, or racial problems, or local policing policy? It sounds like it says something, but when you look carefully at the words, it says nothing at all. Unfortunately, many people have prior experiences of politicians which make them interpret such vague words as being 'manipulative' or judging such statements as 'sound bites', and it is vital to bear in mind that a political context is entirely different to a training, coaching or therapeutic relationship.

Milton language is a framework within which the listener can place their own meaning which becomes totally unique and personal to each listener.

Using Milton language enables you to communicate in a very personal way to a diverse audience, and it also allows a NLP Practitioner to communicate very effectively with his or her clients.

Uniquely and crucially, Milton language enables NLP Practitioners to coach clients without knowing specific details about the presented issue. This means that a Practitioner can help a client to achieve change without having to go into factual details about an issue that could be embarrassing or even traumatic to describe.

Time - Back to the list of topics

Time is an abstract concept, created entirely through our perceptions. Mankind has created many ways to measure the perceived passage of time, from celestial temples and sundials to atomic clocks and wristwatches.

How we relate to time has a great influence on how we relate to our past experiences and future plans, and you may already know someone who seems very rooted in the past or, someone who is forever waiting for tomorrow. Some people say, "I'll look for a job soon", or, "I'll go and talk to my manager when the time is right". Some people say, "This won't work, because we already tried it", and some people say, "It's time to try something new - nothing we do works".

When we consider time as a shared experience, we can certainly observe that different people exhibit different relationships to that shared experience. Consider for a moment the concept of 'now'. When is it? Is it the same for everyone?

Ask a few of your friends the following questions, and notice how their answers differ:

- When is 'now'?

- How long is 'now'?

- Where is 'now'?

- How big is 'now'?

- What colour is 'now'?

- Where is the 'future' in relation to where you're standing?

- Where is the 'past' in relation to where you're standing?

Hopefully, you found their different answers interesting, yet found yourself wondering how that information might be useful. By understanding a person's relationship with time, we can understand their relationship with change and create tools and techniques that make change easy to achieve for them.